Exploring the Link Between Beauty Products and Cancer Risk

Written on

Chapter 1: Understanding Epidemiological Research

Epidemiological studies often appear tedious, focusing on identifying intriguing connections that necessitate further investigation. It's uncommon for these studies to yield findings that significantly impact the general populace. This makes it perplexing to see minor studies gaining media attention frequently.

In 2022, a study emerged that examined the relationship between the use of hair products and cancer. Media outlets highlighted that chemicals in hair straighteners were linked to a heightened risk of uterine cancer, particularly affecting Black women. This raises a critical health issue intertwined with equity, as minority women are more likely to be affected by these potential hazards.

Previously, I discussed this research, pointing out that the results were not particularly convincing. The study resembled a fishing expedition, seeking any correlation without substantial evidence. The authors concluded that "more research is warranted," rather than asserting that hair straighteners definitively cause cancer.

Subsequent investigations by the same researchers yielded similarly inconclusive results. One study suggested a vague link between the use of talc and ovarian cancer. However, a more compelling study titled "Use of Personal Care Product Mixtures and Incident Hormone-Sensitive Cancers in the Sister Study" illustrates the limitations of such research.

The Study

This study was conducted using data from the Sister Study, which involved women who had a sister diagnosed with breast cancer. The participants were surveyed about their use of beauty and self-care products, collecting data on demographics such as race, age, and income.

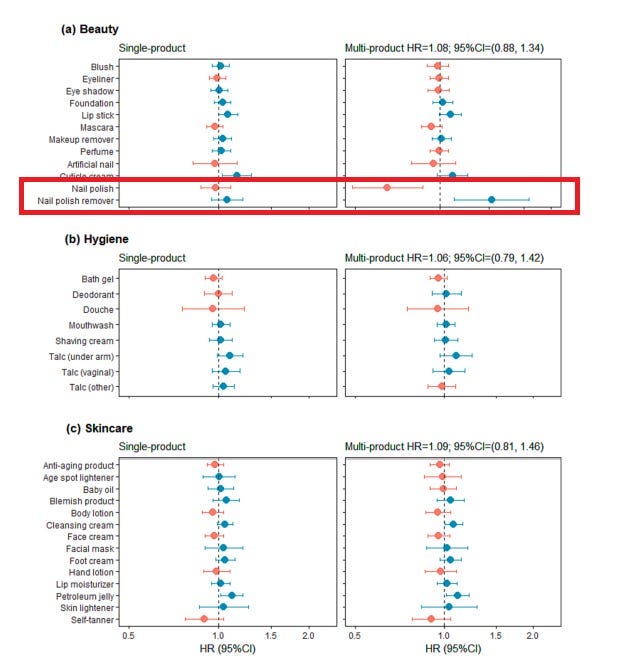

Two key elements stood out in the findings. Firstly, the researchers categorized product use into four arbitrary groups: beauty, hygiene, skincare, and hair. They then explored the correlation between these categories and three types of cancer: uterine, breast, and ovarian. Interestingly, increased use of hygiene products was associated with a higher risk of ovarian cancer, while beauty products correlated with a specific type of breast cancer. Surprisingly, greater use of skincare products appeared to correlate with a lower risk of breast cancer.

However, the strength of these associations was weak, with p-values hovering between 0.03 and 0.05 in a study involving 50,000 participants. These results suggest that the research likely fails to reveal any genuine risks warranting concern.

Additionally, the authors conducted a more granular analysis, evaluating every product in relation to the three cancer types. This revealed some peculiar associations: for instance, women who used more eyeliner reported a lower likelihood of developing ovarian cancer, while those using more makeup remover indicated a higher risk. Notably, nail polish was linked to a reduced risk of uterine cancer, whereas nail polish remover was associated with an increased risk.

The supplementary data presented various models that yielded contradictory results. When adjusting for other product use, the authors found no statistically significant increases or decreases in risk for any individual product.

The crux of the issue lies in the concept of researcher degrees of freedom, which refers to the myriad choices researchers make during data analysis. These decisions can significantly influence the final outcomes, and researchers seldom disclose how different choices might alter results.

The study employed a Benjamini-Hochberg test to address multiple comparisons, but curiously, the significant relationships between beauty, hygiene, and skincare products and cancer were excluded from this correction. Had the authors applied this test comprehensively, it's likely they wouldn't have reported any statistically significant findings.

Bottom Line

The associations drawn from this research are largely inconsequential. If the authors had modified a few parameters in their analysis, the results would likely differ significantly. This implies that advocating for regulation of hygiene products due to potential cancer risks should also extend to skincare products, which may offer protective benefits.

Moreover, the findings may not even meet the minimal threshold of statistical significance when applying the appropriate corrections. This conclusion applies to other studies from this research group as well. Recent analyses suggest no significant relationship between talc or douching and cancer, contradicting earlier claims.

Ultimately, the intent here is not to assert that beauty products are harmless, but rather to emphasize that current research does not provide conclusive evidence of their risks. The significant findings are likely a byproduct of how the research was conducted rather than indicative of genuine health threats.

It's crucial to recognize that the authors are not being criticized; they are following standard practices in epidemiological research. The main takeaway from their initial paper remains valid: further investigation is indeed necessary. Until more comprehensive studies are conducted, we are left with a collection of associations that may lack substantial meaning.

This video discusses the potential risks associated with common acne products, specifically focusing on the presence of benzene, a known carcinogen.

This video explores the implications of toxic beauty products on the health of Black women, particularly for those working in salons and styling hair.