Pathway to Understanding the Cosmos: Leaving Science Denial Behind

Written on

Chapter 1: The Night Sky Unveiled

For those residing in urban areas, spotting between 400 to 800 stars on a clear night is common. However, in less light-polluted regions, such as rural Virginia or parts of Alabama, this number can soar to 15,000.

While many stars can be seen without interference from artificial lights, most of them are relatively close by cosmic standards. For instance, individuals in the northern hemisphere may have never encountered Alpha Centauri, our nearest stellar neighbor, but the dazzling Sirius is merely 80 trillion kilometers away. The light we now see from Sirius was emitted just eight and a half years ago, coinciding with the debut of The Walking Dead on AMC. Polaris, our renowned North Star, is situated 433 light-years from the ecliptic plane, with its light reaching us shortly before Shakespeare began penning The Taming of the Shrew.

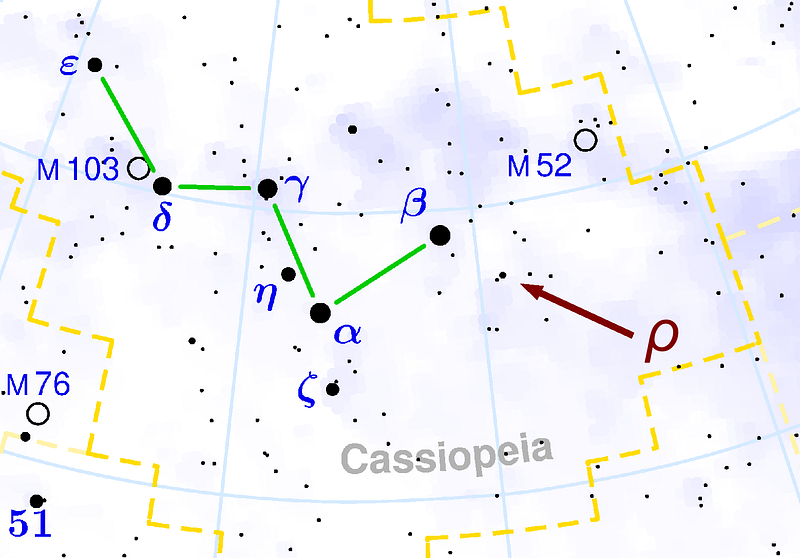

Rho Cassiopeia, a dim star in the constellation Cassiopeia, is located 3,400 light-years away, with its light originating during Pharaoh Amenhotep III's rule. Meanwhile, V762, also found in Cassiopeia, is even more remote; its light began its journey in the 15th millennium BCE, during a time when the Sahara was a lush landscape and the last prehumans inhabited China.

For those in areas with minimal light pollution, the Andromeda Galaxy appears as a fuzzy shape. The photons from Andromeda began their trek towards Earth 2.6 million years ago, a period during which Homo habilis was just beginning to develop stone tools.

Chapter 2: Confronting Creationism

As someone raised in a creationist environment, I recognized early on that the time required for light to reach us from distant stars posed a significant challenge. We were taught that the Earth and the universe were created instantaneously just 6,000 years ago, dismissing the scientific consensus surrounding the Big Bang. Faced with only 6,000 years for light to travel, the starlight issue stood out as one of the most glaring contradictions to the young-earth perspective, ultimately driving my curiosity in physics and contributing to my eventual departure from creationist beliefs.

Initially, many creationists devised various explanations to sidestep this dilemma. One of the first I encountered suggested that just as God created trees with roots and rivers with channels, He could have similarly created a universe filled with starlight, allowing the first humans to witness distant stars from day one. This reasoning appeared straightforward and was easily digestible in a Bible study setting. However, anyone with even a basic understanding of astronomy would find it lacking. The night sky is not a mere static display of points of light; it is a vibrant, evolving tapestry. We observe pulsars in rotation and witness the light from distant stars shifting and fluctuating as it is obstructed by exoplanets. We even see nascent stars expelling long streams of superheated gas:

In 1987, keen observers in the sky witnessed a supernova explosion in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a neighboring galaxy. Neutrino detectors globally recorded the first invisible signs of the supernova hours before its light became visible. This event allowed us to observe the death of a star nearly 170,000 years after the explosion occurred. To suggest that all these phenomena are merely God's way of "filling the universe with starlight" is untenable; it implies that everything we perceive from over 6,000 light-years away is simply a cosmic façade, a light show of events that never transpired.

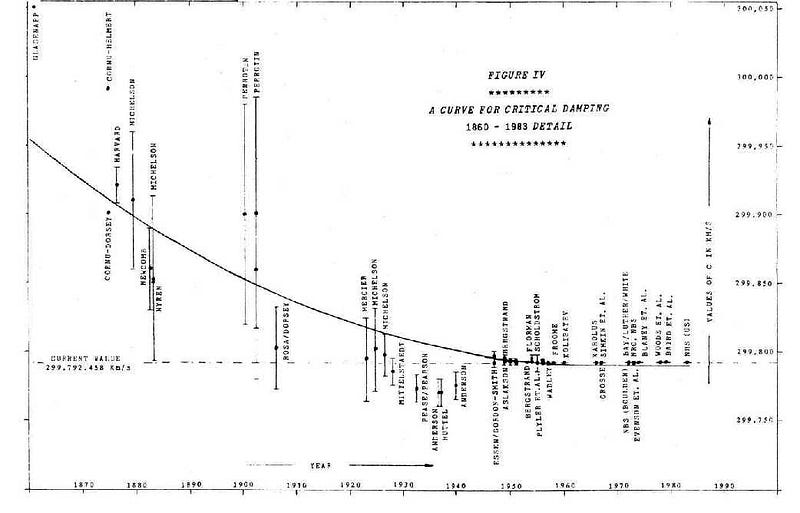

Some creationists, like Barry Setterfield, proposed a more unconventional idea: that the speed of light was greater in the past, perhaps exponentially so. This theory suggested that light from the farthest reaches of the universe could have reached Earth quickly but slowed down to a near-constant rate in recent times. In a 1981 article, Setterfield selectively used early measurements of light speed from the late 19th century to create a fitting exponential decay curve, conveniently suggesting that the speed of light approached infinity around 4,004 BCE.

Despite initial excitement, this idea was met with skepticism from other creationists. We understand that the speed of light is fundamental to the very essence of spacetime; any variation in this speed would drastically alter the existence of atoms and molecules. Furthermore, if light speed had indeed changed, distant pulsars would have recorded this alteration, as observing the cosmos means looking into the past.

The quest for understanding was a personal fascination for me. At a creation science conference in the late 1990s, Dr. Russell Humphreys suggested a different approach: the possibility that time operated differently across the universe, allowing light from distant galaxies to reach us while only a few years passed on Earth. This theory, known as "white hole cosmology," briefly gained traction among educated creationists but eventually faltered due to severe mathematical errors and misapplications of special relativity.

The cycle of explanations continued, each increasingly inventive than the last. This mirrors Ken Ham's assertion in the documentary We Believe In Dinosaurs, where he claimed, “You should listen to our PhD experts talk, even though you won’t be able to understand anything they say.” This statement encapsulates the movement's strategy: creationism does not need to prove its claims, only to maintain an appearance of scientific legitimacy. Their goal lies in controlling the narrative, using science to preserve their authority, and as long as they can maintain that their pseudoscience is "just as plausible" as mainstream science, their interpretative power over Scripture remains intact.

Chapter 3: Seeking Truth

Despite the allure of creationist explanations, my quest for truth demanded more. I sought solid, testable hypotheses, ones that could withstand scrutiny and evolve over time. Scientific progress occurs not merely from the emergence of new theories but from those that successfully explain both previous failures and successes. This drive led me to major in physics, allowing me to explore these theories thoroughly.

Over time, my commitment to learning deepened; I immersed myself in geology, biology, and astrophysics, consistently exhausting my inter-library loan limits. I was searching for a common thread that would explain why fields like astronomy, geology, and evolutionary biology excelled in making accurate predictions and aligned so well with one another.

Yet, the challenge of starlight and time never seemed to yield a straightforward resolution. My transformative moment occurred in 2014 when I encountered a Hubble image that fundamentally altered my perspective.

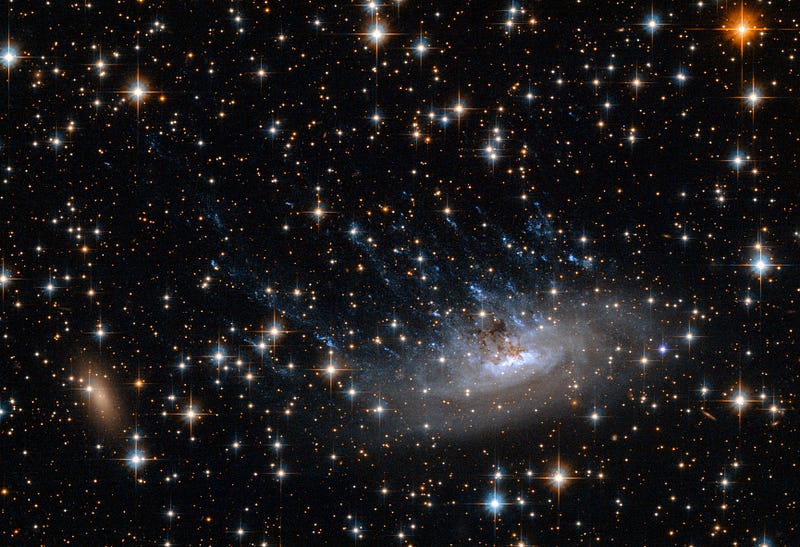

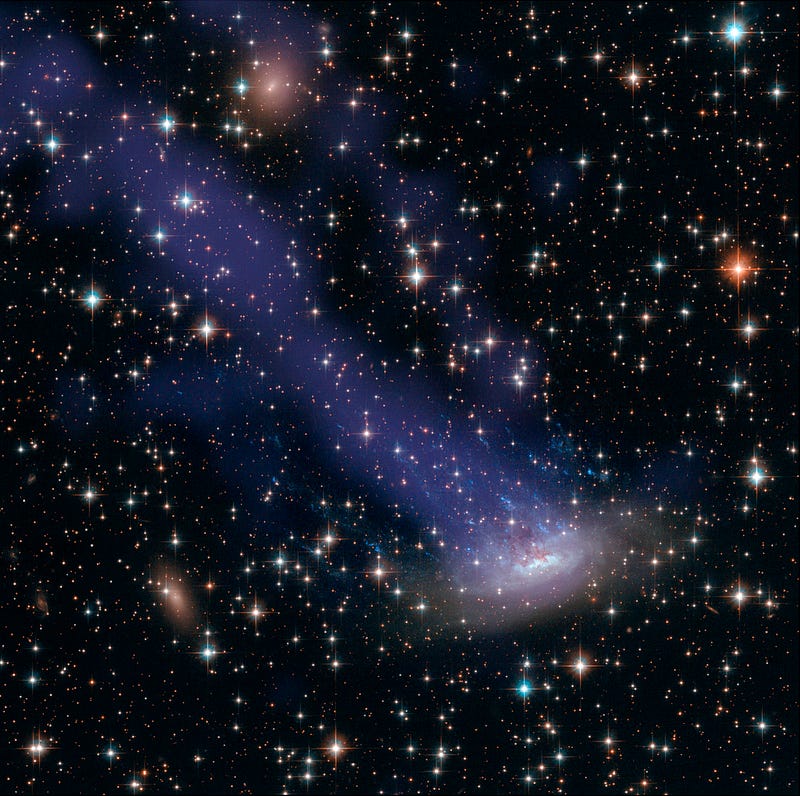

The image depicted ESO 137–001, a barred spiral galaxy located 2.1 quintillion kilometers away, hurtling towards the center of the Norma Galaxy Cluster at an astounding speed. The question that arose for me was obvious: how long had this dynamic motion been occurring? This photograph, originating from 220 million light-years away, dated back to the time of early dinosaurs. Even if I were to dismiss the starlight dilemma and assume the light was arriving in real time, it still posed a formidable challenge. This represented genuine motion on an intergalactic scale. If the universe were merely 6,000 years old, how far could such a galaxy have traveled?

As I delved deeper into the narrative, I realized the first image I had seen was just visible light captured by Hubble. Astronomers had also utilized the Chandra X-ray Observatory to image the Norma Cluster, unveiling a significant trail of superheated gas disrupted by the galaxy's rapid descent into the cluster's core.

This moment crystallized everything for me. To assert that light could somehow travel infinitely fast to reach us was already an extraordinary claim, but the existence of a trail stretching 280,000 light-years was irrefutable. I could not fathom how an entire galaxy could traverse that distance in just 6,000 years. The universe simply could not be young, and my previously held beliefs began to collapse.

If I had encountered the same image a year earlier, I doubt it would have had the same impact on me. My departure from creationism was a gradual process, shaped by years of absorbing new information and challenging my preconceived notions. It was merely a matter of timing that led to my epiphany.

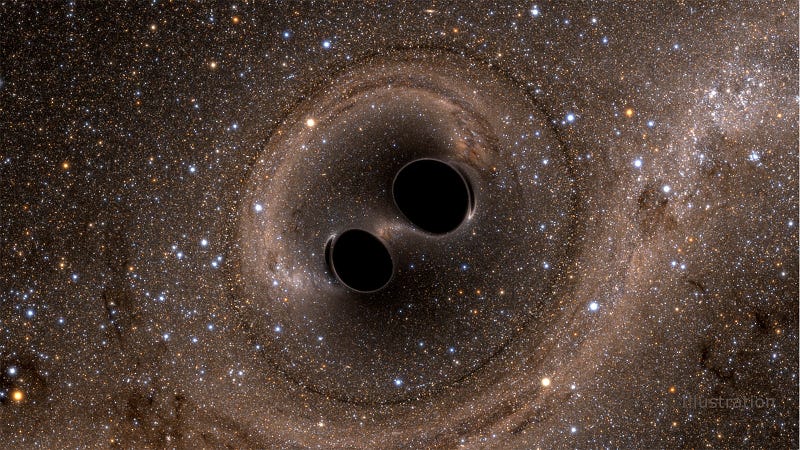

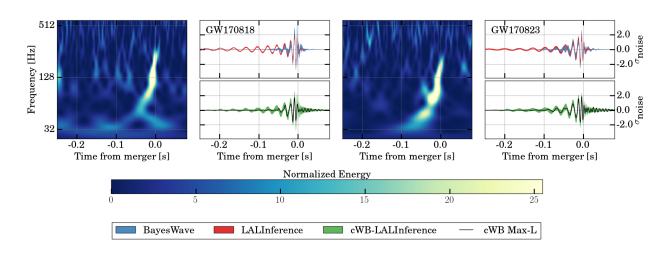

In 2018, the LIGO gravitational wave observatory detected the ancient collision of two massive black holes. This extraordinary event transformed an immense amount of matter — five thousand times the mass of Jupiter — into pure energy instantaneously, producing a powerful gravitational wave that traveled across the cosmos.

This wave had originated from a galaxy 2,750 megaparsecs away — an astounding 8.9 billion light-years from Earth, indicating that it predated our Sun. This morning, however, LIGO detected a gravitational wave from even further back in time.

This ripple in the fabric of space began its journey while the Milky Way was still forming, continuing through the epochs of solar fusion, the birth of the planets, and the dawn of life. As it traveled, it witnessed the rise and fall of species, including the dinosaurs, and every moment of human history, culminating in its arrival today.

Chapter 4: Embracing the Truth

During my time as a creationist, I was incapable of grasping the significance of these discoveries. I would have dismissed the detection of a gravitational wave from billions of light-years away as a mere error or a misunderstanding, needing reinterpretation. Everything before the last moments of cosmic history would have been conveniently ignored. Had I remained in the realm of science denial, I would have missed out on the profound beauty and complexity of the universe, which makes creation all the more awe-inspiring.

In conclusion, the journey from creationism to scientific understanding opened my eyes to the wonders of the universe.

Science is real, and the real world is magnificent. David MacMillan, a freelance writer, paralegal, and law student in Washington, DC, features in the 2019 documentary We Believe In Dinosaurs. His upcoming book will delve into the impact of science denial in America and his personal journey away from it.